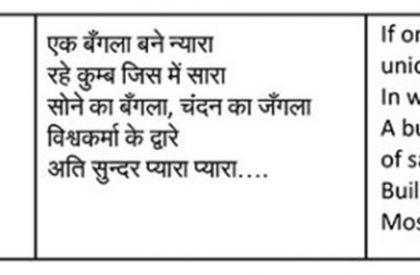

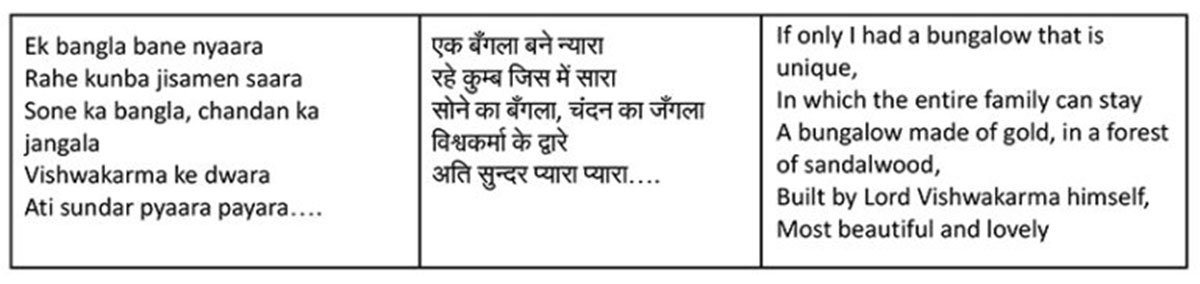

In 1937, when Kundan Lal Saigal sang the song “Ek bangla bane nyara…”, little did he know that it would become an instant hit. To the few people who listen to Vividh Bharti’s ‘bhule bisre geet’ or Saregama Caravaan (the antique radio lookalike), songs of K L Saigal are still beautiful. One cannot really say if it was his unique voice or the tune of the song that made it popular. What we are interested in, are the lyrics of the song, which roughly translate to – “If only I had a bungalow that is unique….made of gold, in a forest of sandalwood”. There is no doubt that this line defined the aspirations of not only the 1930’s, but those of every generation that followed.

The word ‘Bungalow’ comes from the Hindi word bangla (बंगला) and Urdu بنگلہ, literally meaning ‘in the Bengal style’. The Merriam-webster dictionary describes it as a one-storied house with a low-pitched roof and usually a front porch. The closest meaning of the word ‘nyara’ is unique. So, the actor in the film wishes for a ‘unique’ house made by Lord Vishwakarma (God of Building) himself, a house for the ‘entire’ family. Where does this aspiration come from? What does a house mean to us and why is it so valuable? When does a house become a home? In this series of articles, we will explore the various associations we have with our homes and how the physical structure of the house has created them over time. Many studies speculate that in the coming decades, Asia will need to build houses for more people in its urban areas than the rest of the world combined. If this is the case, let’s talk about what it means to have a home.

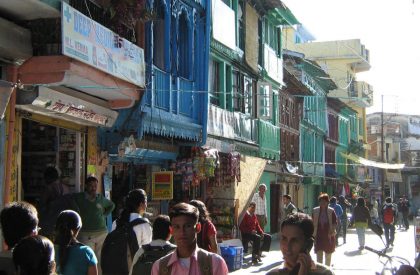

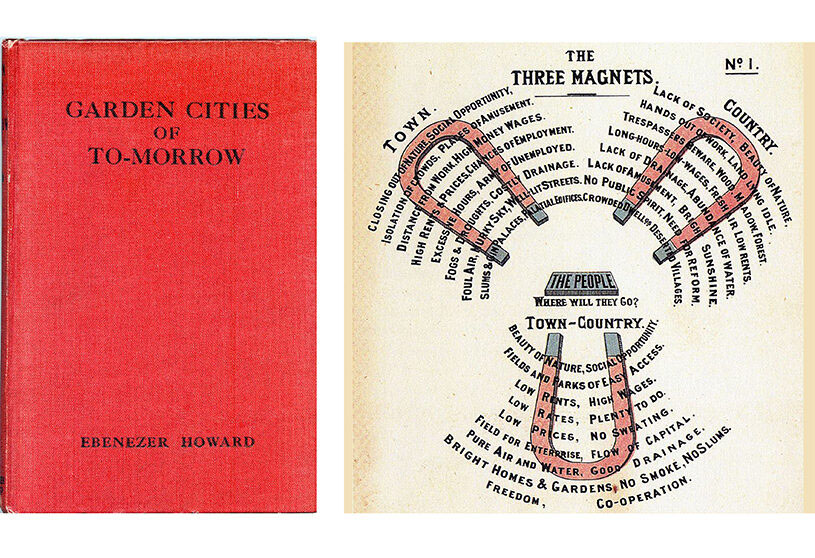

If we think of homes as merely places that we live in, then the only function they serve is that of containers or shelters. However, a quick reflection will convince us that our houses do many more things than just providing us with shelter. Any human activity, be it language, music, literature or buildings, is in essence, a relationship between place, culture and techniques. All aspects of the culture of a time, like ideas of individuality, privacy, family relations, politics and society are reflected in the making of a home. One might have experienced this while walking down a street in any old city, as one imagines the life that people led centuries ago. Our home, like our identity, is always in the making. It is an indicator of ways of life through time.

We as humans have two opposing desires coded within ourselves. A psychologist may be able to better explain this, but we shall try nonetheless. We want to be unique and at the same time, belong to a group or a community of some sort. This is partly because we not only identify ourselves as individuals but also as part of a larger group. So, like the Saigal song, when we say we want to make something ‘nyara’ or unique, we are not necessarily saying that it has to look different. We are actually talking about changing the relationship between place, culture, and techniques. The subsequent lines of the song are exactly that metaphor – ‘sone ka bangala, chandan ka jangala…’. The very act of taking a precious metal that we adorn our bodies with and putting it on a building, changes the way we look at buildings.

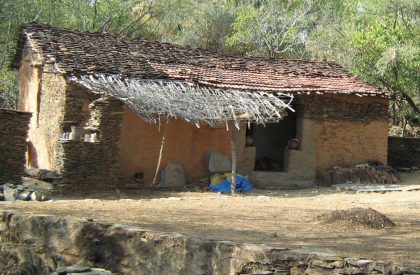

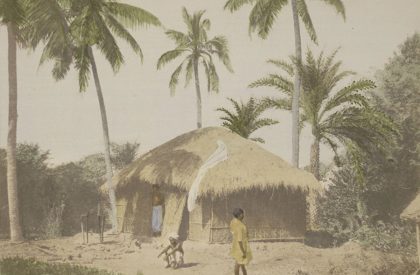

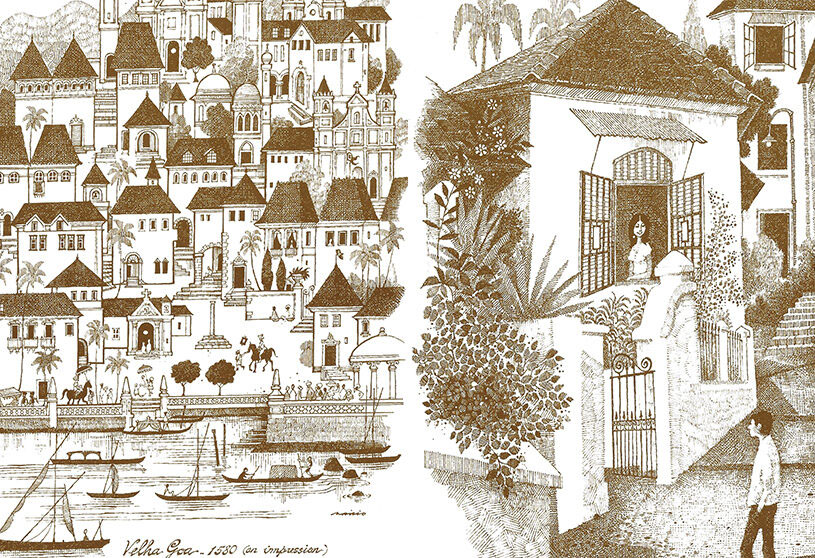

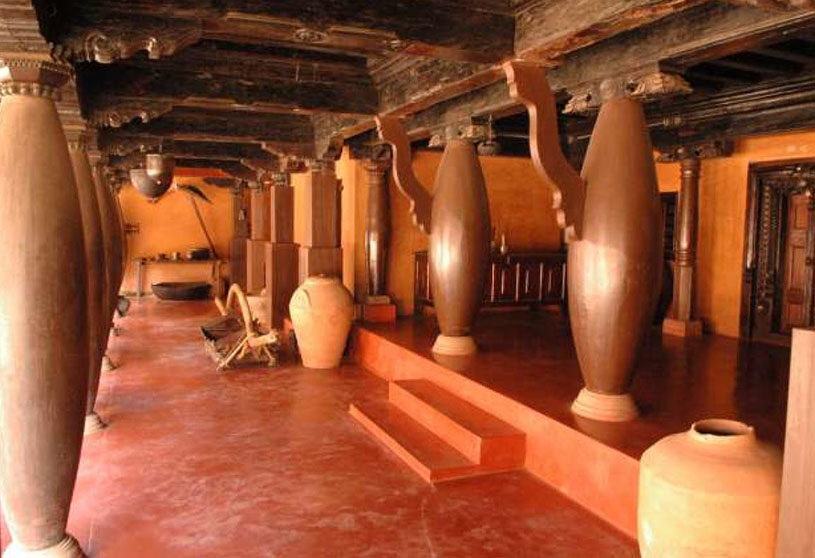

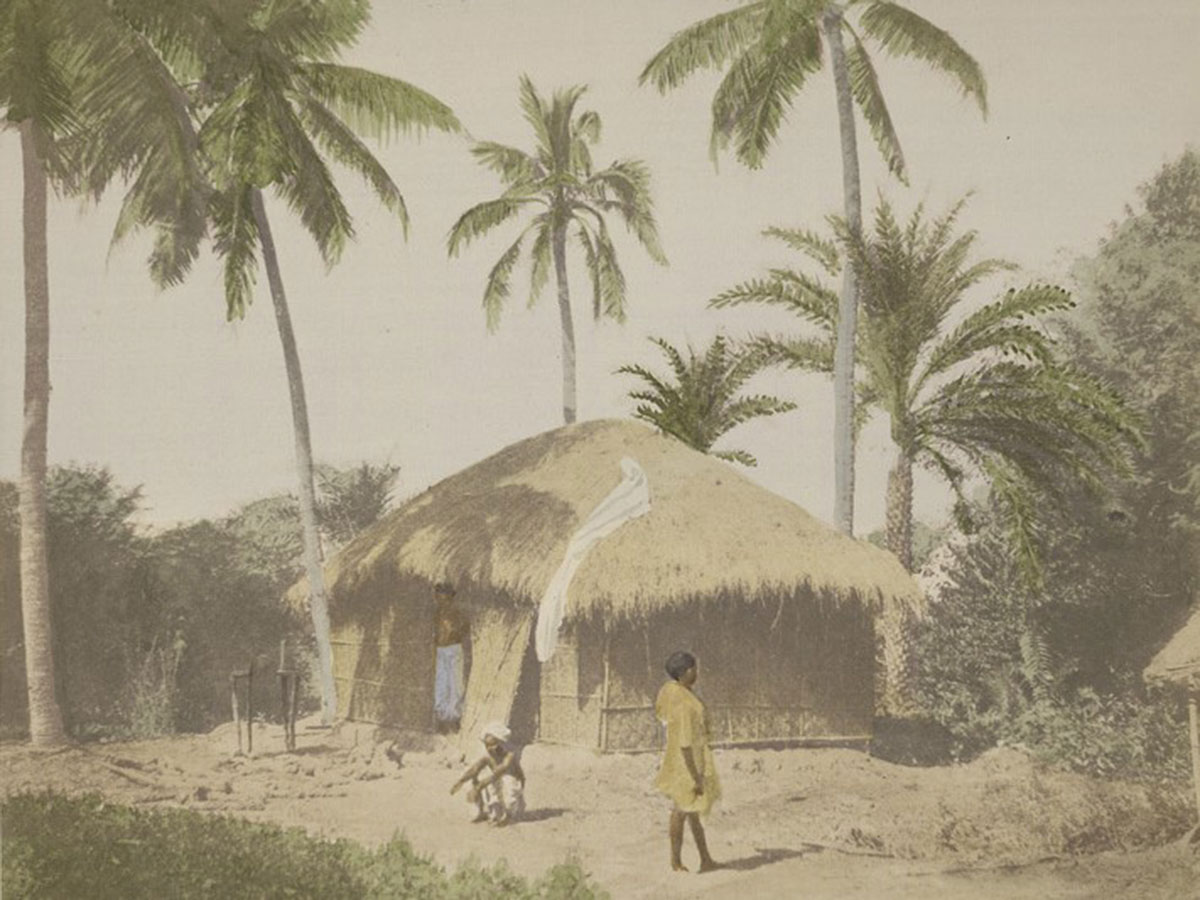

Palaces, forts, temples and other monuments have a longer life span than residential architecture in India. This phenomenon of disappearing traditional houses like haveli, wada, bhunga etc across India is multi-fold and very complex with multiple actors and stories. The ‘Bengal Hut’ (Fig. 2) is one such example of a traditional house type. A large portion of India’s population still lives in these simple buildings like the Bengal hut. The materials with which the dwellings are made has changed but the form or the layout has not undergone dramatic transformation. It was this humble hut with its overarching roofs and shade on all sides which led to the development of the bungalow. This type was particularly favoured by the Europeans in India who found India to be quite hot.

In this series of articles, we shall try and focus on spaces and elements in our houses that remind us of our ways of life. While we may not live in a traditional house, we still have certain associations, use certain words and arrange things in ways that have roots in practices from centuries ago. The importance given to a threshold, the location of the kitchen and water storage and the words we use for storage areas, have in them, remnants of culture and time. Vaastushastra, which still decides the layout of many Hindu homes, is another form in which these associations are carried forward. While its interpretation is debatable, its role in shaping residential architecture in India cannot be ignored. In this series, we hope to bring out our associations with homes by taking clues from Bollywood songs, regional poetry, TV advertisements and folk culture. We shall explore some ideas around homes, neighbourhoods and cities over the next few articles.

Till then, keep looking and keep thinking because just like 2007 Asian paints advertisement, ‘Har ghar kuch kehta hai…..ki andar isme kaun rehta hai’ (Every house tells a story……of who stays in it).