“He sat in defiance of municipal orders, astride the gun Zam-Zammeh, on her old platform, opposite the old Ajaibgher, the Wonder House, as the natives called the Lahore Museum.”

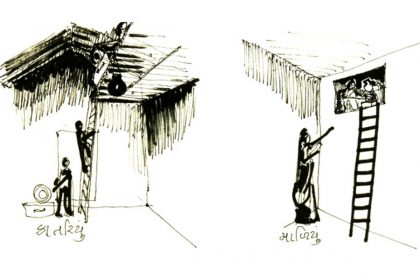

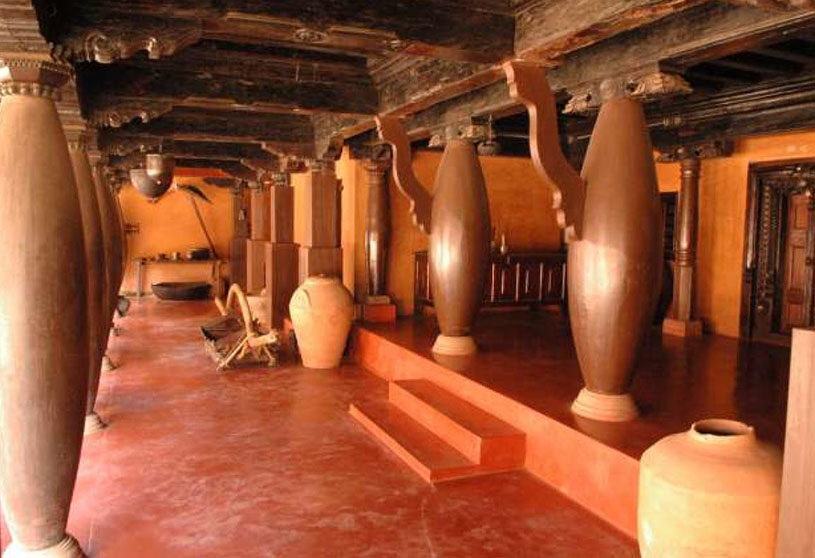

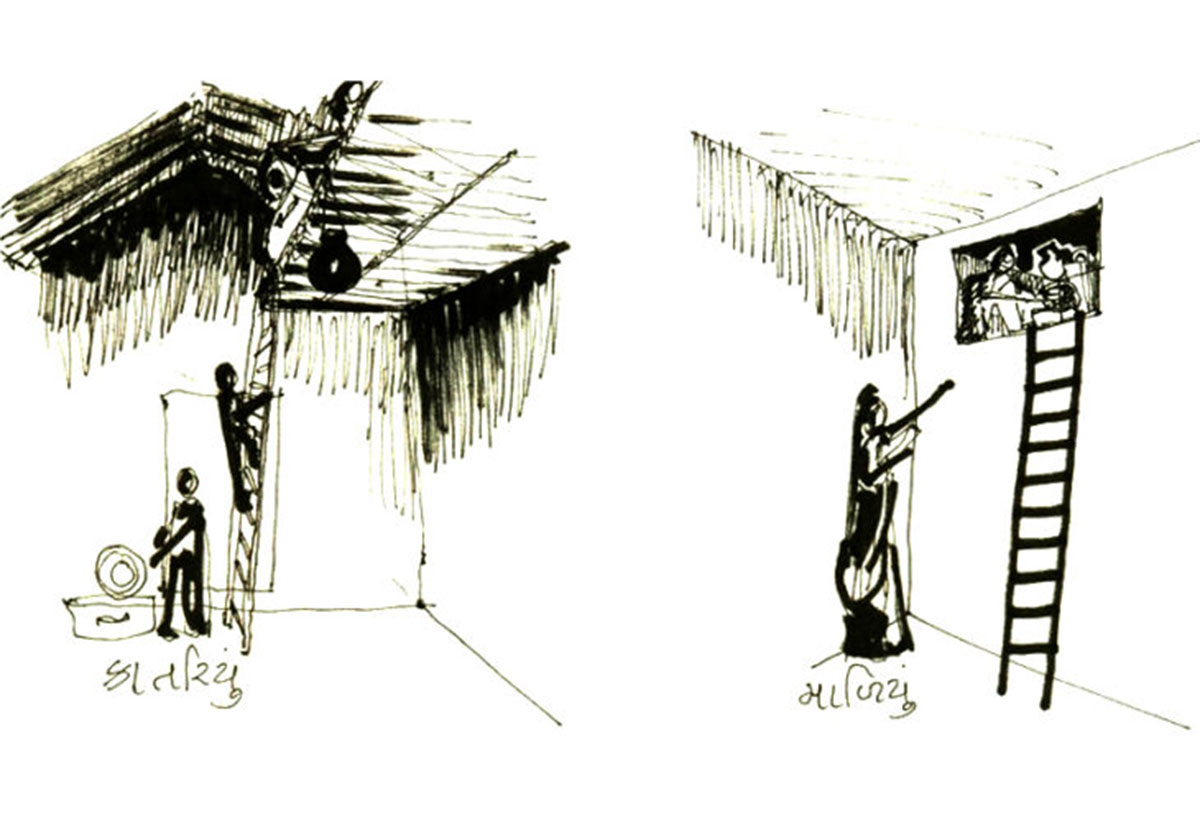

These were the opening lines of the novel Kim, by Rudyard Kipling, author of ‘The Jungle Book’. Here, the word ‘Ajaibgher’ or ‘ajeeb-ghar’, referring to a museum, literally translates to strange house or wonder-house. Long before museums were built in India, traditional Indian houses had their own ajaibghars. For a young child growing up in such a house, the ‘katariyu’ became the ajaibghar. Katariyu, the space below the sloping roof in traditional Gujarati homes was essentially a space for storage. There are several such spaces that evolved or disappeared over time. This article is about some such spaces.

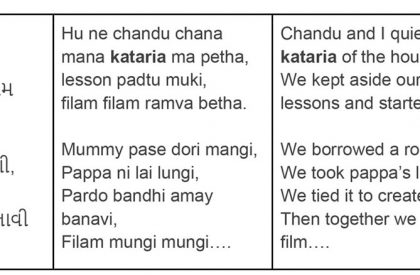

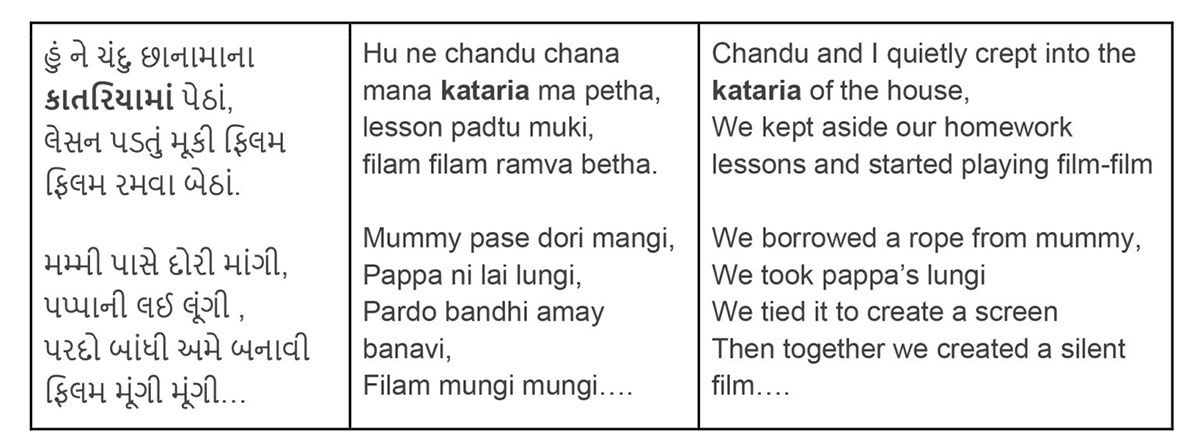

There is a Gujarati children’s song by Ramesh Parekh, that beautifully brings out one’s association with the katariyu as something more than storage – as a place of creativity and fun.

‘Katariyun’ roughly translates into an attic, which doubles up as a hidden place for children to play. In the above song, children turn ordinary unused spaces into that of play and fun. Given the rarity of sloping roofs and changes in lifestyle, not many plan and build a katariyun today. There is storage space (like a ‘maliyun’ or loft) provided above bathrooms as an afterthought, but actively planning for a katariyun is a rare phenomenon. Today, we store different things, smaller things that can be accommodated in drawers below the bed, in cupboards, under the kitchen platform or in TV cabinets. Few houses store grains and pickles for year-round consumption. Old items are disposed to make room for new ones. In traditional Gujarati homes, objects old and new were stored in the Katariyu with the hope of putting them to use in the next season. Akin to a museum or ‘sangrahalay’ (a place to collect things), the Katariyu was a place full of curious objects. It served as a fertile ground for reimagining use through play.

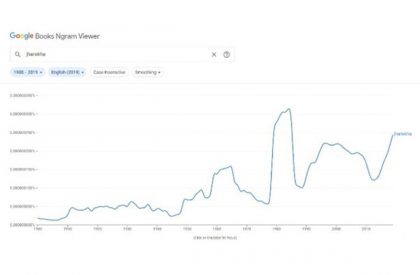

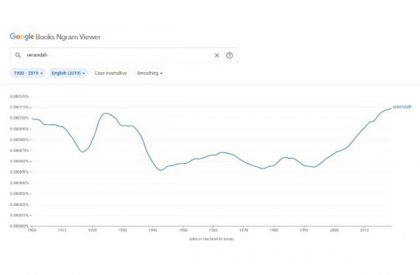

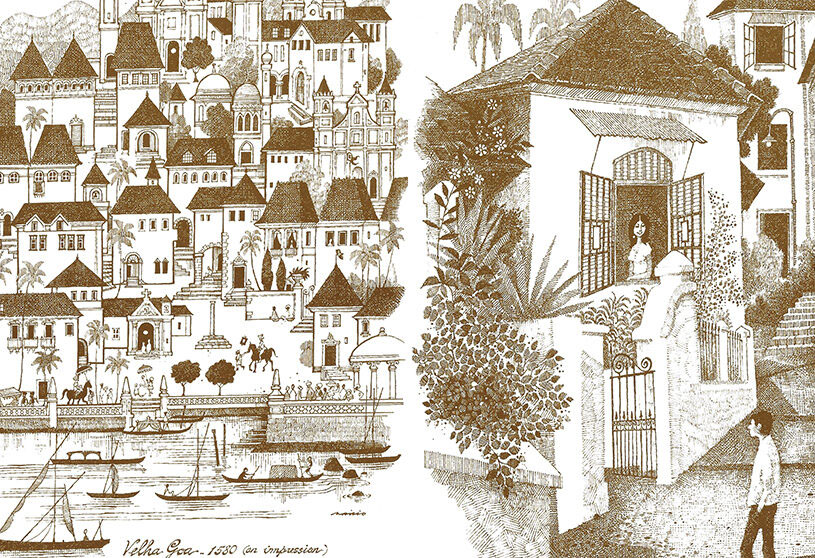

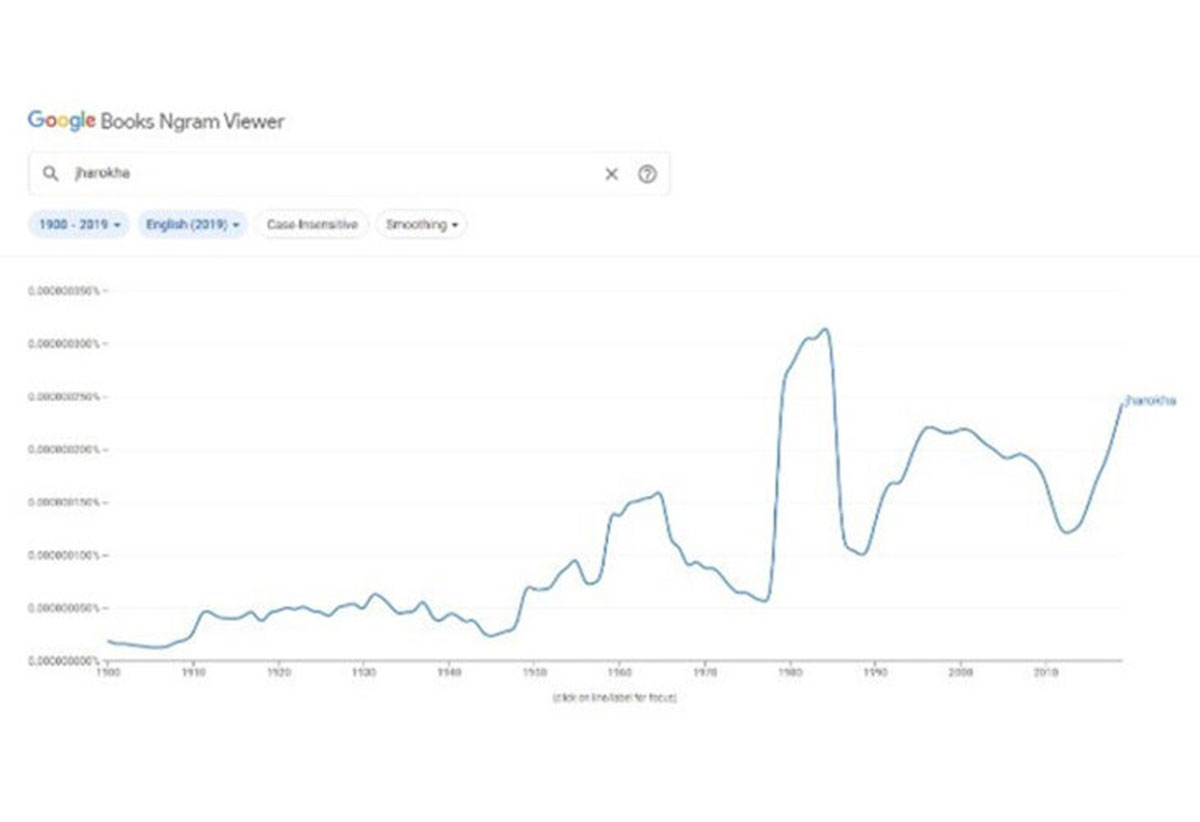

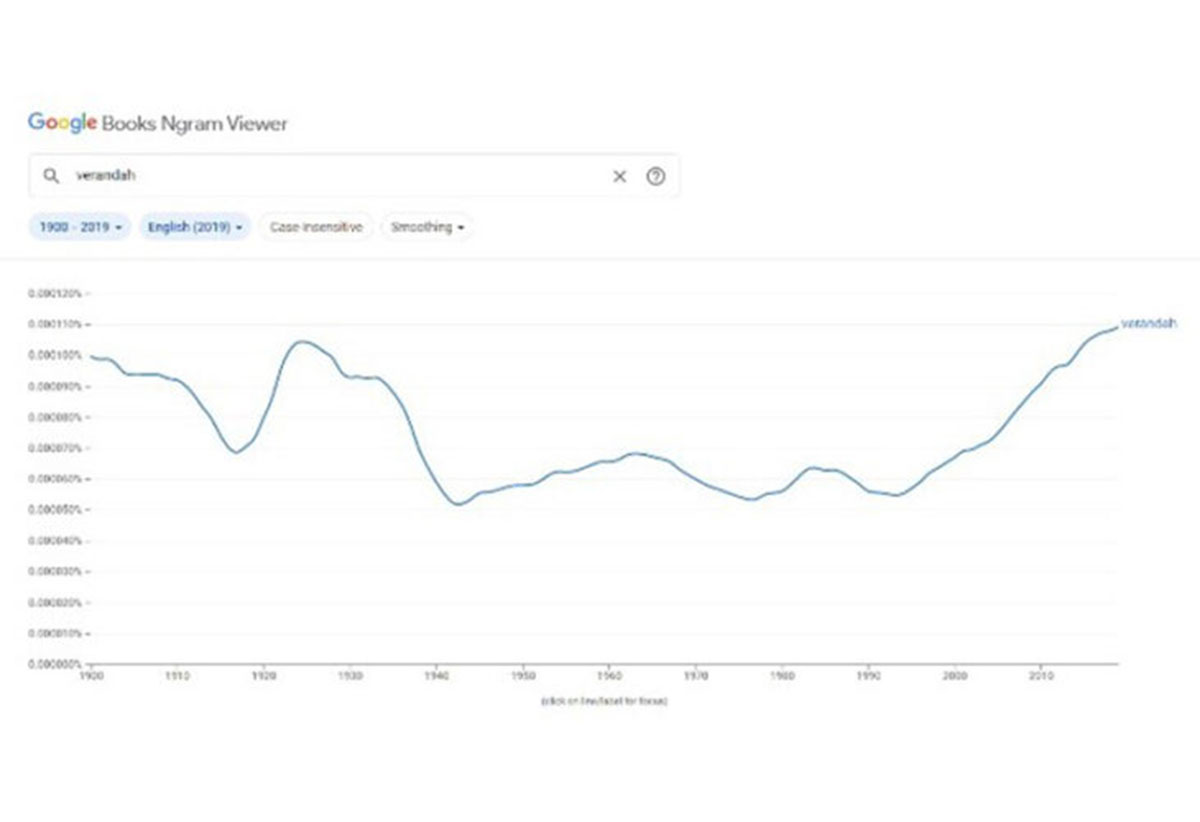

Chowk, jharokha and paniyarun are other examples of such disappearing spaces. With growing density, smaller plots and issues of security, the chowk (or courtyard), an open to sky private space inside the house, is now rare to find. Around the world and throughout history, the courtyard has taken several forms. In India too, courtyards are found in different shapes and sizes from Leh to Kerala. The jharokha, a protruding enclosed balcony like space, was very common in the North-west region of India. With its intricate carving, it not only provided privacy, but also highlighted the facade of the house. It was a place from which to see and not be seen. Most balconies in Indian homes today double up as places to dry clothes or possible future expansion. The size of a jharokha was such that not more than 2 people could sit in it. It was an intimate space. If we look at the number of times words like ‘jharokha’ or ‘verandah’ are written in books or magazines, we see a positive growth which makes us hopeful. The more we talk or write about these spaces, the more popular they become. Higher are the chances that we might value them again and reinterpret them to accommodate different lifestyles.

The paniyaru was specifically found in the hot and dry regions of north-west India. It was a place where earthen pots and sometimes metal pots were placed for the purpose of storing drinking water. It was mostly located in the central part (near the courtyard) of the house. It became a prized possession in a place where water was scarce. So, like any valued commodity, it was guarded, given high importance and protected. It was common practice for a diya (a lamp) to be placed at the paniyaru as part of the daily puja. This was done to express the blessing of drinking water for the household.

Change is inevitable. Everything undergoes change. Architecture is one of the last indicators of a changing society. Other art forms like music, fashion and literature change much faster. Riyaz Taiyyabji, an architect and educator in his article ‘Education at SA, Ahmedabad: Framing an Architectural Value System’ outlines different aspects of change and their pace. He points out that material culture, which includes skills, techniques, technology and operative procedures is the fastest to change. The fashion industry is a case in point for this. It is said that fashion almost changes every month with new kinds of clothing constantly replacing older ones. The next to change are habits. It takes a few months to form a habit. Take the simple example of wearing a mask before going out in public. While it was quite a change to remember wearing a mask in the initial months of the pandemic, only now is it a default action. The next to change are customs. This is slow as it takes an entire generation to come up with their own ways of doing things. The last thing that is slowest to change are values. Values like respecting nature, caring for animals and fellow human beings, respecting elders or even for that matter valuing happiness over money are examples of principles that are at the very core of our being. It takes several generations to change these values.

Architecture is affected by each layer of change from material and technology to cultural values. In a sense, the built environment is a tangible indicator of societal change. The disappearing spaces in Indian households is a sign of changing societal relationships. Rahul Mehrotra, while talking about modern architecture in Chandigarh, made an excellent point that clarifies this idea. He spoke of how in India, ‘aesthetic modernism’ came much before ‘social modernism’. We started making standing balconies, standing kitchens and walk-in closets in our buildings before we had nuclear families or a capitalist market driven economy. On the other hand, the utility area in our flat is still called a ‘chokdi’ (a small chowk where all the washing happened), a section of the kitchen platform below the aquaguard is still the paniyaru and our balcony is our jharokha.