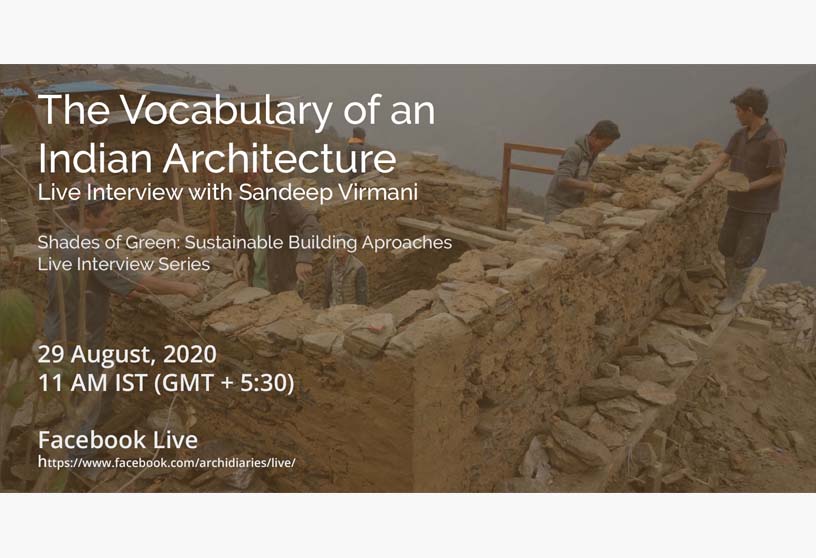

In the fourth interview of the ongoing series of Shades of green, we present to you talk between environmentalist and architect Sandeep Virmani and Mohammed Ayazkhan. This interview series is a place where we talk to various practicing architects about sustainability and its different approaches in architecture and design.

Sandeep Virmani is an environmentalist, with training in Architecture. Based in Kutch, over the past 30 years he has worked with communities all over India, celebrating their traditional knowledge in water management, food production, animal breeding, and seed conservation, building with natural materials, and wildlife conservation. He has set up two organizations, Hunnarshala Foundation to work with built habitats and Sahjeevan to work with various indigenous communities and their ecosystems. He has recently begun writing stories and painting.

In the presentation, we see Sandeep Virmani’s building perspective parallel to the journey of his work. At the onset of the presentation, he talks about his influences, following them with his introduction to rurality by documenting it, and later his projects that have been and are in realization. The talk takes us through the various possibilities of work that were discovered and documented by his works and how his learnings came together in the form of the Hunnarshala Foundation and Sahjeevan.

(Early influences, Working on new capital for Haryana)

(Early influences, Working on new capital for Haryana)

Sandeep started the presentation at the beginning of his career, the time after he graduated from Chandigarh school of architecture. As a newly graduated architect he went on to work for Aditya Prakash, for planning a new capital in Haryana, he experienced Chandigarh and questioned what could be done better in a planned city. Talking to the migrants, milk suppliers, and cart-pullers, people who used their hands, they started planning a city that worked for everybody.

“What a real Indian city should look like? It included the sector approach, and it had a village in the center of every sector, this village would not only provide food, but it would also provide services that were mainly done by hand…poultry, animal husbandry, agriculture, repairing, etc…This fascinating idea got me thinking of what India could be and what Indian architecture could be”

After moving from Chandigarh, Sandeep went on to work with Laurie Baker and shared his experience of working with him.

“Here was a person who worked with the artisans in an equal way, to the extent that he credited them for the architectural interventions he was able to develop.”

(Early influences, Gandhi’s autobiography)

(Early influences, Gandhi’s autobiography)

”India lives in her villages, if you don’t understand Indian villages and Indian rurality, then you won’t understand India”-M.K.Gandhi

In talking about Gandhi’s famous quote we see where his spirit and efforts were headed as he offered to be a part of the working team for Golana social housing for Dalits under Indira Awas Yojana. Living in the village and working closely with the Dalits who were also building the houses they were going to occupy under the scheme, Sandeep realized the power of knowledge in these communities. The shared sense of identity of the community was clear in the way they worked, not as a team but as one person itself.

The experience from this project was the turning point where he decided that he wanted to work beyond just housing or architecture and start understanding rurality and what is its relation with nature and technology.

(Geo-hydrology based solutions for Khari village)

(Geo-hydrology based solutions for Khari village)

(Geo-hydrology based solutions for Khari village)

(Geo-hydrology based solutions for Khari village)

Sandeep started Environment traditions and Sahjeevan in 1991 and began to work in Kutch. As they studied the villages, Sandeep shared with us the rural dictionary of understanding the geology of the village which helped them create a well that supplied the villagers with an annual supply of sweet water. This well was then used as a model, which was developed on a larger scale also leading more than 100 villages to develop local solutions for the scarcity of water.

(Characteristics found in traditional seeds)

(Characteristics found in traditional seeds)

Sandeep shares with us his intense documentation, about rainfed seeds and the seed keepers, telling us about the interesting barter system of seeds now set up in the form of seed banks by them. Further expanding on the documentation he tells us about how grasslands are important to us in arid regions. Their documentation of the banni grasslands was in close conversation with the local pastoralist (dhannitachat) community from which they identified 12 different dominant species in this grasslands and started mapping the whole region. After documenting the grasslands Sandeep and his organization have worked closely to revive the grassland, and now it has started attracting a lot of biodiversity.

“Sitting in one room they (villagers) mapped the whole grassland of 125 km, their dominant species, and where they grow…so these twelve species were identified. Later on, we asked them if the grassland had changed at all, and then they made us a map of the trends of change of the region, and what are the threats to the grasslands and what do they think will happen to it in the next twenty years?”

(Mapping threat to the grasslands)

(Mapping threat to the grasslands)

(Fakirani Jatt community, migrated from Afghanistan)

(Fakirani Jatt community, migrated from Afghanistan)

Sandeep introduces to us the Fakirani jatt community, which migrated from Afghanistan to Kutch. This unique community breeds camels that survive at a junction of mangrove and arid ecosystem, which is found at the edge of Pakistan and Kutch and also in places in Afghanistan. This ecotonal species, a species that can live at the edge of two ecosystems, has been rebred by this community for centuries. This community is a specialized one that lives and roams with this species, hence they have lived off the camel milk. Sahjeevan worked with Fakira ni jatt to get the National animal recognition board to recognize Kharai Camel as a distinct breed.

(Ecotonal Camel species, bred by the Fakirani Jatts)

(Ecotonal Camel species, bred by the Fakirani Jatts)

After this recognition, the community was even closer and protective of the mangroves and camel species. So, when some companies started coming in and removing the mangroves, this community filed a case with the help of the Sahjeevan organization against the companies. After winning the case in 2019, the community has now started re-planting mangroves in addition to selling Camel milk as a product to Amul. This set a tone for Sahjeevan to go further forward and work with other such communities that breed such indigenous animals.

After the 2001 earthquake in Kutch, Sandeep joined the Hunnarshala foundation. Hunnarshala started as a foundation where collaborations and associations were built after the 2001 earthquake in Kutch to capacitate people for the reconstruction of their habitat. They reached out to the Dekhbhal community in Banni grasslands. This community lived in Bhungas, which were not majorly by the earthquake, which led them to question why the bhunga typology had better survived the calamity

(Sham-e-Sarhad, Redeveloping the Bhungas)

(Sham-e-Sarhad, Redeveloping the Bhungas)

“In an earthquake, when there is lateral thrust, these lateral thrust when applied to a square, the walls start breaking and the corners collapse. In a circle, there are no corners, so it allows the forces to rotate in a circle and go into the ground.”

After the earthquake, Hunnarshala helped this community to remake 1200 bhungas which were constructed completely by women. They also went on to build a resort called Sham-e-Sarhad which brings in a revenue of 50-60 lakhs and is used to uplift the community. This project led them to document many other traditional seismic-safe technologies throughout India.

“In Kashmir, you have isolated foundations and nailless wooden houses and dhajji walls, in Uttarakhand you have containment reinforcement for stone walls, in Himachal Pradesh, you have floating column homes, in Spiti, you have rammed earth and wooden corner reinforcement, and in Bihar and NE, you have bamboo homes, all of these are techniques to make sure that earthquakes do not break their homes. We have only started this documentation and these techniques have been developed by the communities.”

Through Hunnarshala, Sandeep and his team have worked with several such communities and the government to redesign these traditional building technologies for the government-provided housing. In the process, they identified the different needs of the community and threats according to the geography, and also documented

not only traditionally used materials, but also the tools and technology behind them. He introduces us to the following communities and the way of living:

The Fakirani jatt who build woven homes with mats, the Oads, who build cob houses that have lasted over hundred years, the Bhil community, that makes rammed earth houses, the Dabiyas, who work with bamboo using wattle and daub technique in multi hazardous regions, the Madhubani regions and their attic homes, the Uttarakhand houses, which have stone masonry with mortar that is bound by a wooden frame, the Muzaffarnagar homes with brick roofs.

(Woven homes of Fakirani Jatt community)

(Woven homes of Fakirani Jatt community)

(Construction with Cob, Oad community)

(Construction with Cob, Oad community)

(Rammed earth construction with Bhil community)

(Rammed earth construction with Bhil community)

(Building homes in Tibet, post-earthquake)

(Building homes in Tibet, post-earthquake)

(Building brick ceilings in Muzaffarnagar)

(Building brick ceilings in Muzaffarnagar)

Learnings from all of these places have helped them to redesign better homes with the same material and technology that was previously used by them. In the process we also notice how Hunnarshala uses the learnings from one area to benefit another region as in examples of the Nepal earthquake, they used techniques from Uttarakhand, Learnings from Muzaffarnagar are similar to ones in Haryana. Hunnarshala has taken all of this further by trying to standardize some of these techniques as in the case of rammed earth walls, where they have worked with artisans to develop and test rammed earth walls that are now used in a standardized manner for any laterite soils. Throughout all of these examples, we see his constant efforts in understanding the inherent knowledge that the community has developed over years, and using it in a way to benefit them. In some of the cases, this work has also led to the upliftment of these communities, as in the case of the Dabiya community, who gained confidence and employment for over 200 homes that were made by the government of Bihar.

(Patels community housing, Bhuj)

(Patels community housing, Bhuj)

Further, Hunnarshala has worked with housing in Bhuj, Gujarat, and Ahmednagar, Maharashtra, building homes for 200-300 people who earlier lived in slums. In these projects as well we see the work that they do with the communities, recognizing the patterns they live in and protecting it while giving them the potential to grow.

(Substandard treatment of construction laborers and artisans)

(Substandard treatment of construction laborers and artisans)

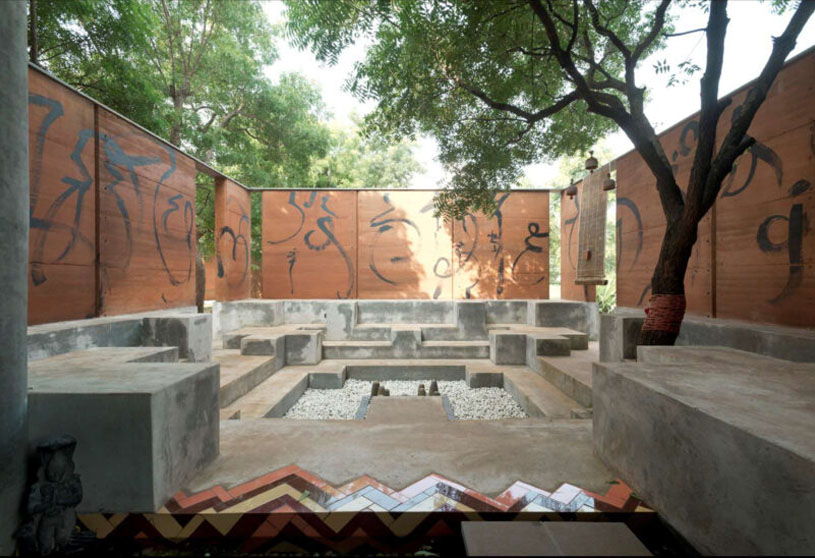

Sandeep addresses the issues that artisans face when they try to come to a city and offer their skills. The conditions that these artisans are substandard and hence Hunnarshala gave them a platform to show their skills and creativity in a manner that gives them equal recognition to an architect. In several other cases, Hunnarshala has been pivotal in helping these artisans form independent organizations that provide their services to other architects.

In conversation with Ayaz, we see the discussion of the biodiversity of our country, and the difference between the caste system and the tribal system. This difference between what is classical, the vernacular, and the mystic, mystic or tribal is something that we are uninformed about.

“We have two systems here, one what we call the caste-based system and the other is the tribal system. The Dalits, the cased based society, are the artist of our country, they build and serve the upper caste, whereas tribal communities have a completely different way of looking at the world..they teach the next generation how to do everything…from taking care of the farm, the animals to building a well, very few people know about the second category… it’s like comparing classical music, with folk music. The caste system is like classical music, the folk is more the tribal community.”

“The caste-based society believes in ritualized systems, the classical architecture believes in permanence, whereas the folk architecture is ephemeral, it believes that life changes completely, constantly, so don’t fight nature, just go along with it.”

The enthusiasm on Sandeep’s face when he talks about the several practices developed by the communities shows the passion embedded in years of his work. The discussion goes on to talk about how every different region has its version of vernacular or folk architecture and how in most places around the world the need for bringing everything into a monetized economy has changed these cultures.

In telling us his experience with working with the bureaucracy, government officers, he shares with us how the system can be adverse to the kind of work that his organization has done.

“It is like talking to a wall, but sometimes the wall has ears. There is always a bureaucrat, government officer, IAS officer whom you resonate with who agrees with the way you think…Earlier when I was younger I used to get very angry but once I realized that they are a victim of the system, as the people in the villages or I am, I learned to become more tolerant. In the process they become more tolerant too, as long as you don’t get angry with them and empathize with their situation, they are willing to work with you on a humane level and they transform.”

“We have had the opportunity of working with politicians and bureaucrats..as long as the community is with you, the politicians or bureaucrats find it very difficult to do anything, for example, the pastoral community where mangroves had been removed, the community was the one that did all the work, we had just guided them through the process. We have worked on many such cases and won against the government at various times.”

Talking about the interventions and the participatory approach, he reveals his perspective of being a human first and a professional later.

“When we go into villages the first thing we do is we only develop relationships, we begin to start appreciating them, we become aware of the greatness that they have always had and recognized it, then they open up immediately and then when you start discussing professional matters with them, there is a very different trust level, and then you can achieve a great level of work.”

The organizations that are founded by Sandeep give us an insight into what rural communities want. In a time where the first solution that comes to one’s mind is economical support, Sandeep focussed on the knowledge that they had gathered and passed on through generations. He further talks to us about his underlying approach through his work through the example of the Bannis.

“The moment when the buffalo developed by the Bannis was recognized, these pastoralists came back home transformed…They said you didn’t work on our economies, you worked on our knowledge systems, on our pride and after that, we have been able to achieve so much with them.”

In Sandeep Virmani’s work, we see the potential in Indian rurality and in documenting and constructing with their knowledge. It inspires us and helps us to look at things from an artisan’s perspective. His tenacity to empower these communities and make them see the power of their skill is contagious. The presentation even though a concise version of his efforts leaves us astonished and curious.