“I do not want my house to be walled in on all sides and my windows to be stuffed. I want the culture of all lands to be blown about my house as freely as possible. But I refuse to be blown off my feet by any.” said Mahatma Gandhi in his article titled ‘No culture isolation for me’ published in Young India in 1921. While ‘my house’ or ‘my country’ or ‘my self’ is at the forefront of this statement, it is the boundary or ‘walls’ that he wished to be porous, so the ‘culture of all lands’ can be ‘blown about’. At the same time, he wanted the boundary to be strong enough to keep him on his feet. In a physical sense, the space that demarcates and connects the inside to the outside and the private to the public is called the ‘threshold’ of the house.

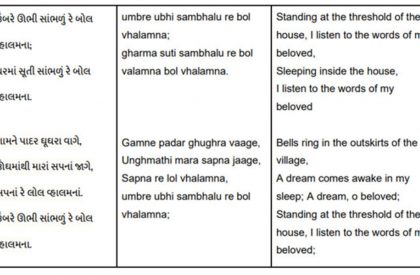

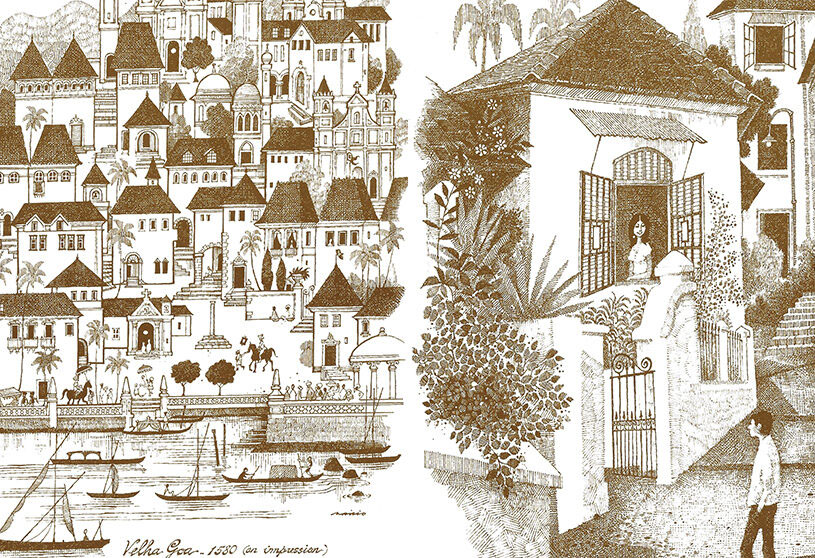

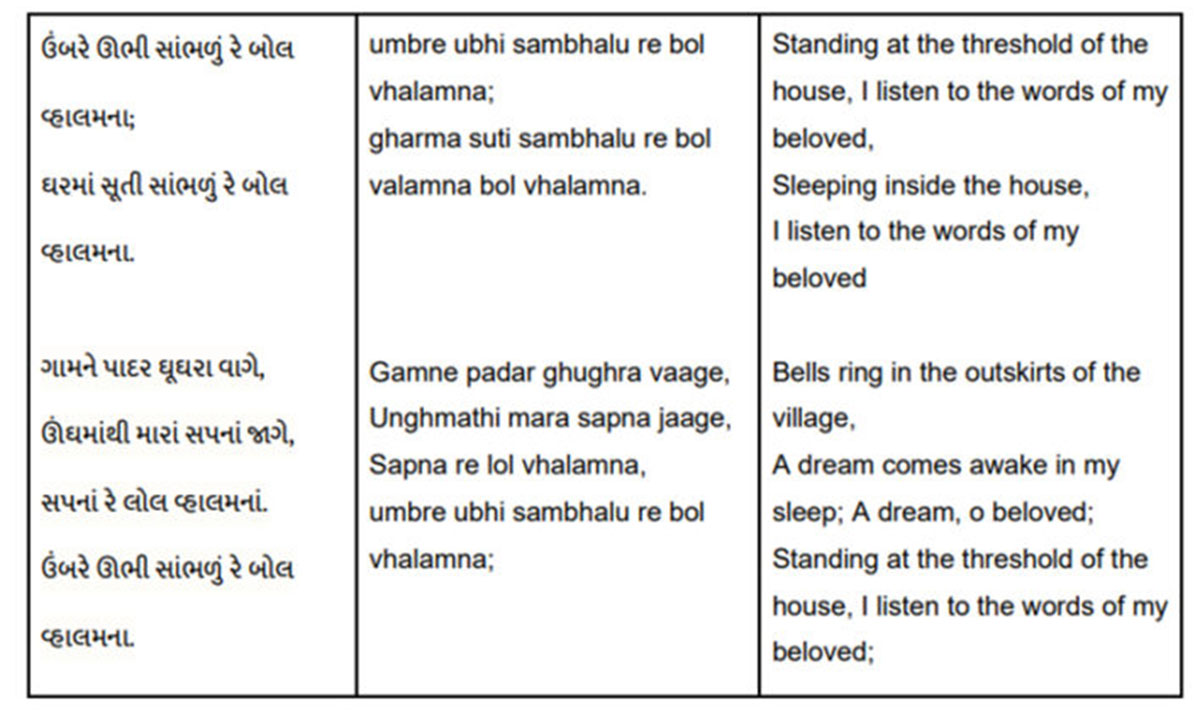

There is a folk song in Gujarati that begins with the words “Umbhre ubhi Sambhloon re bol Vhalamna….”, which roughly translates to, “Standing at the threshold of the house, I listen to the words of my beloved…”. The Umbhro in Gujarati, Umara in Kannada and Chowkhat / Dehleez in Hindi, is the horizontal member of the main door frame that is fixed to the ground. Traditionally this threshold was made from the trunk of the auspicious Audumbar tree (Ficus racemosa), from which it gets its name.

As architects, we are engrossed in the perpetual quest of making good boundaries – inside-outside, plot boundary – building boundary, public-private etc. In the above song, the threshold is not just the physical boundary of the house, but also a social boundary for the woman who is dreaming of being with her beloved.

Another interesting mention of the threshold is in the all so famous story of Hiranyakashipu, an asura / demon, and Prahlad, a devotee of Lord Vishnu. Hiranyakashipu is granted a boon of immortality, according to which, death can never come upon him inside or outside his house, during neither day nor night, on the ground nor in the sky, by the hands of neither man nor animal and by the use of no weapon. To save Prahlad, Lord Vishnu takes the form of Narasimha, who is neither man nor animal. He comes upon Hiranyakashipu at twilight, on the threshold, puts the demon on his thighs (neither earth nor space) and using his nails (neither animate nor inanimate) as weapons, he kills the demon. This story brings forth the significance of the several ‘in-between’ spaces we inhabit in the physical, mental and spiritual world. One also observes this in-between-ness in the way one season transitions into another.

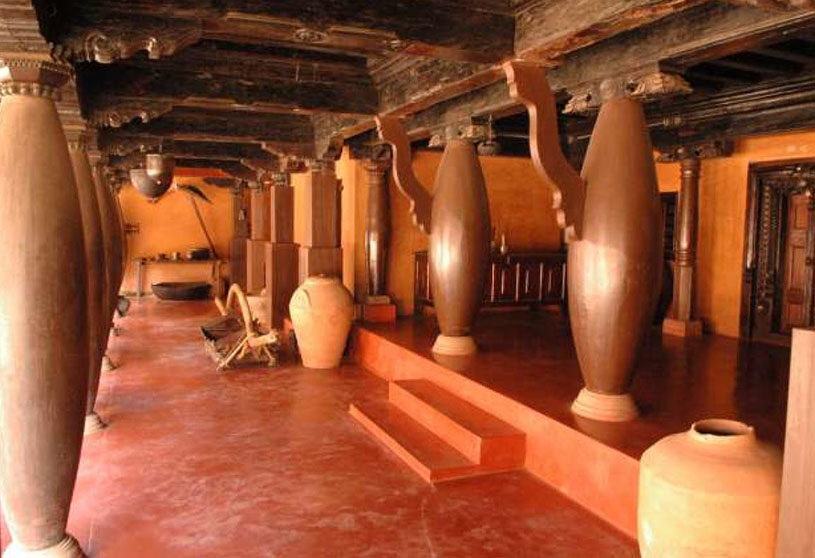

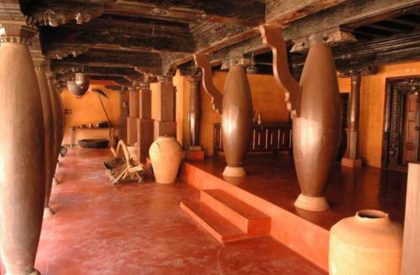

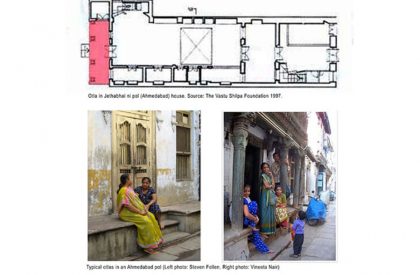

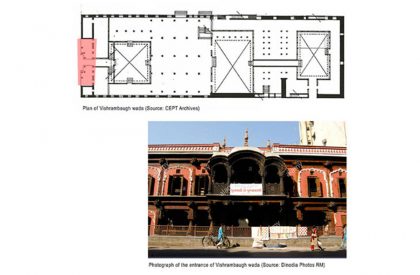

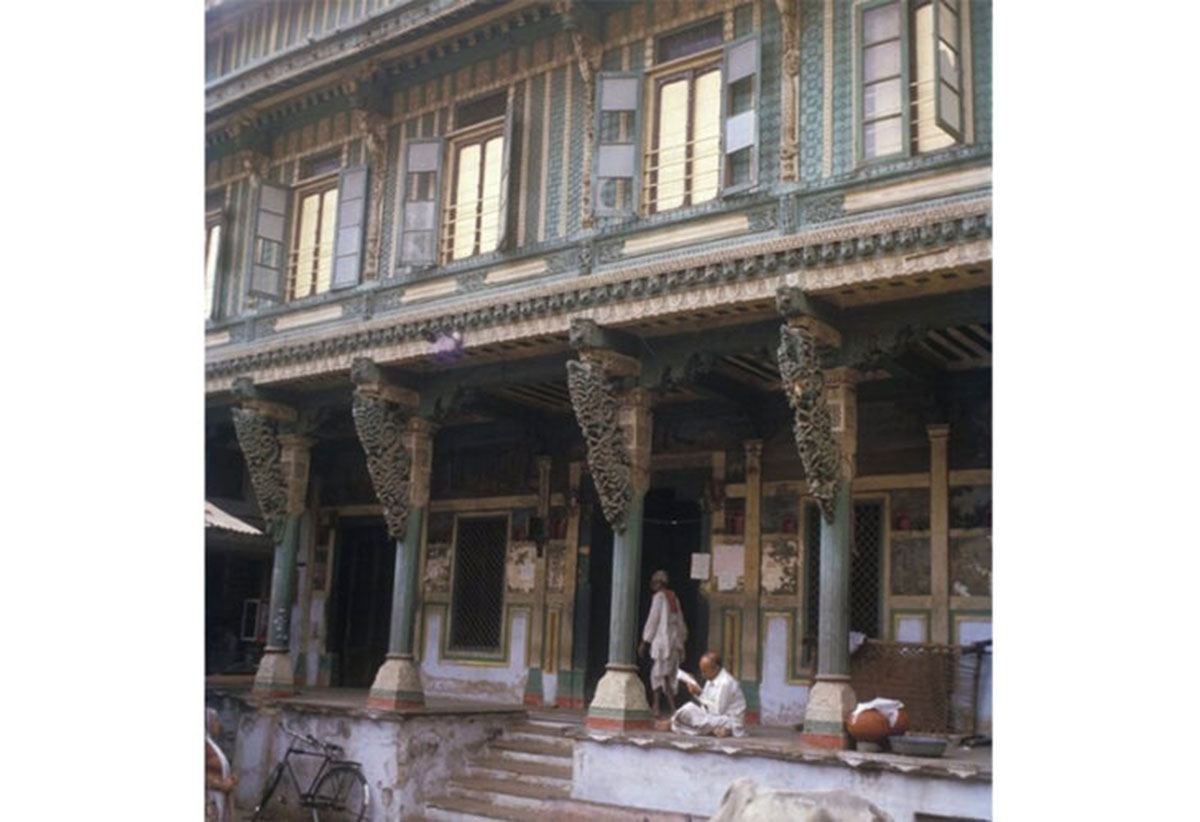

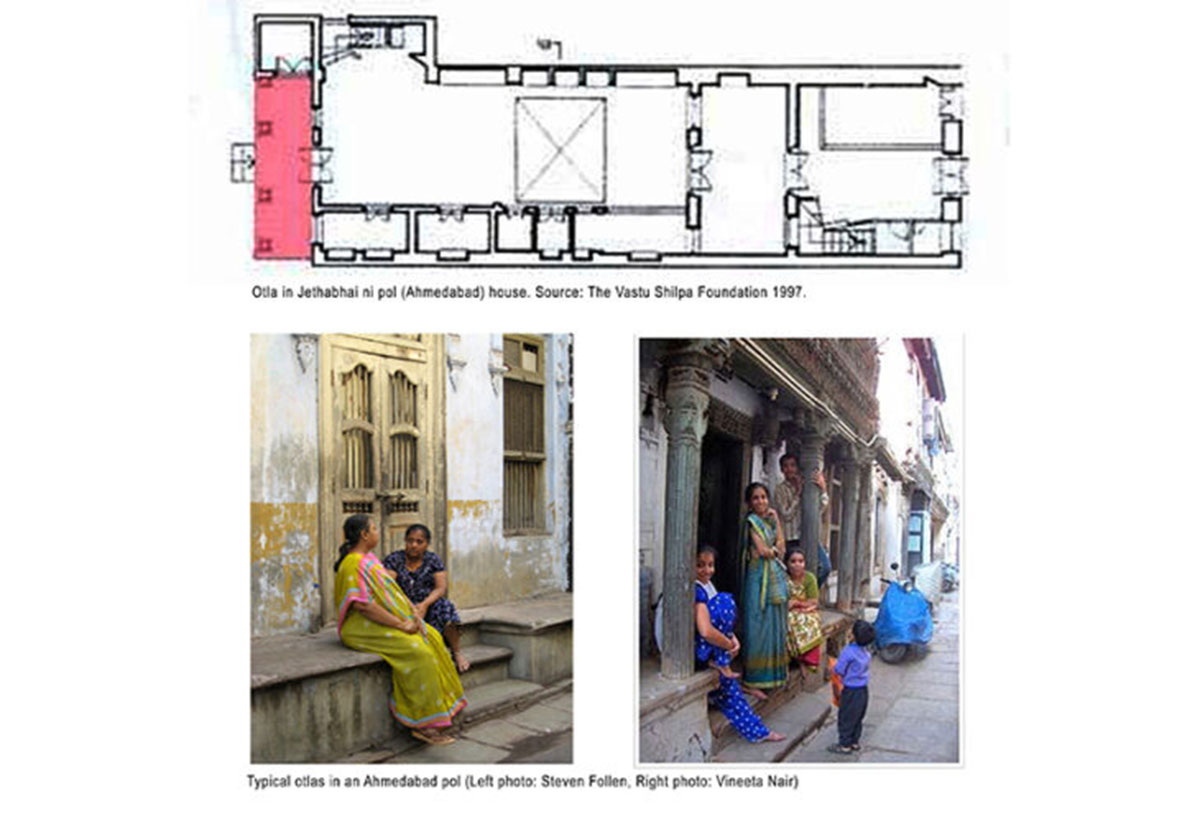

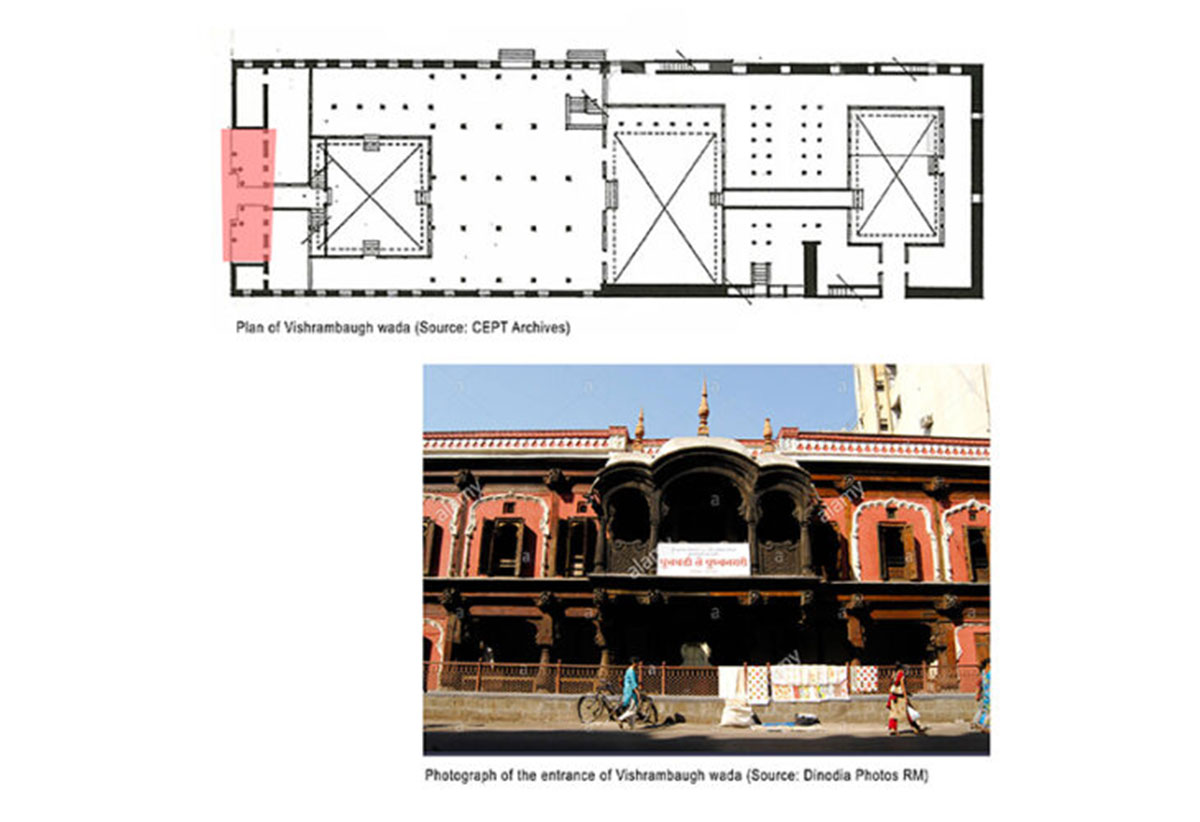

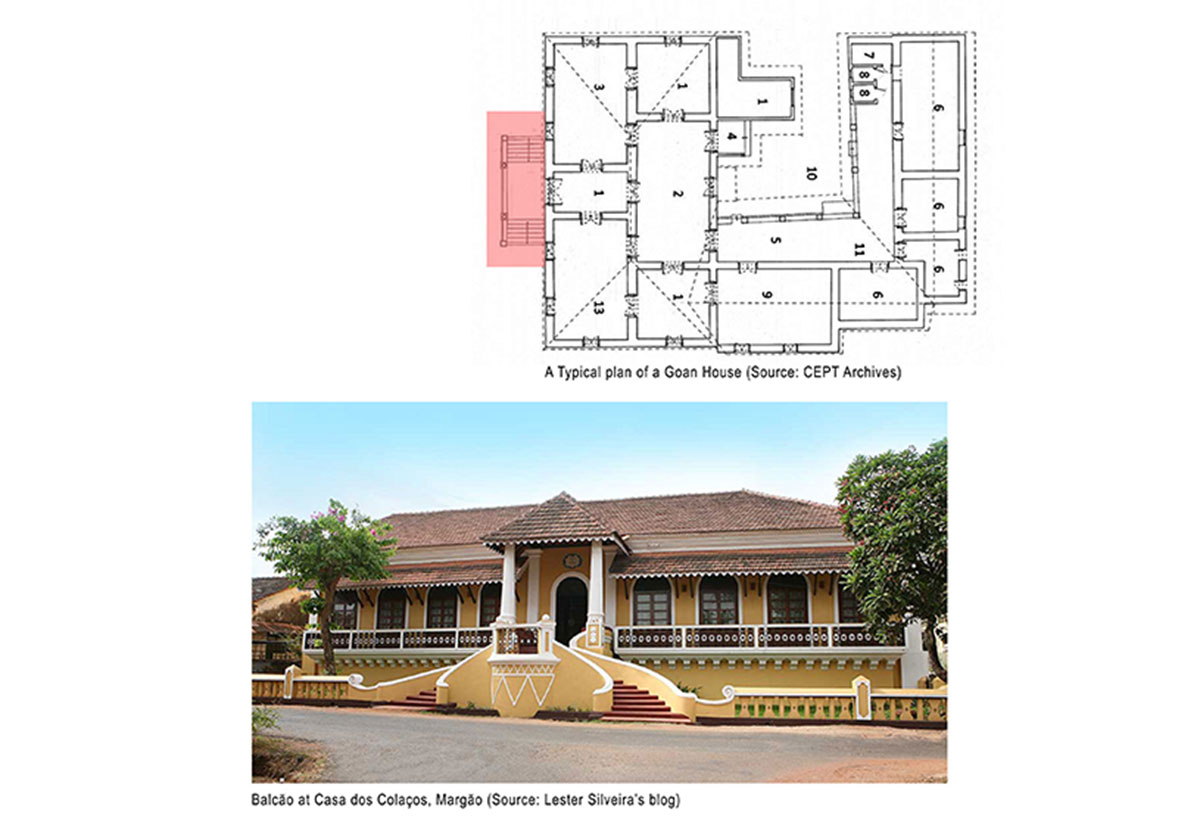

In traditional Indian houses, the threshold did not directly connect to the street. Instead, a shaded verandah-like space was created to further blur the boundary between the house and the street. The Gujarati ‘Otla’ / ‘Osri’ and Marathi ‘Padhvi’ are examples of such a space. In her book on Bohra houses of Siddhpur, architect Madhvi Desai writes, “At one level, it (the entrance) is an architectural solution to the problem of connecting the dwelling to the street. At another level, it is full of social meanings symbolizing welcome, auspiciousness and status.” For example, in houses from the Konkan region, the entrance verandah was stepped, with the higher level (Osri) occupied by family and close relatives, and the lower level (Padhvi) meant for the public. This was one of the ways in which social hierarchy took shape in the houses of landlords. This is similar to the ‘diwan-e-aam’ and the ‘diwan-e-khas’ in Mughal palaces. Otlas, however, were also part of smaller houses that faced commercial or busy streets. Here, they became a space for interaction, quieter than the busy street and separate from the house. These spaces played a great role in building a sense of community in neighbourhoods.

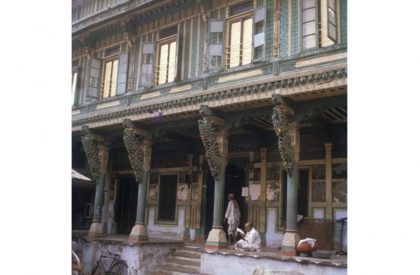

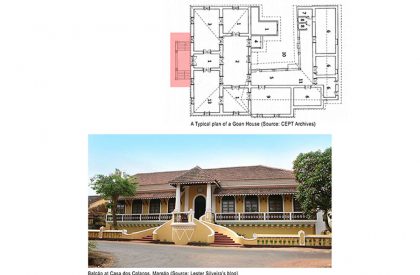

At the upper level, thresholds take the form of windows, jharokhas or balconies. While the word ‘balcony’ has its roots in Europe (the most famous one being the Romeo-Juliet balcony), it exists in different forms in traditional Indian homes. It is more private than the Otla and is meant for looking out onto the street rather than getting to it. British-American Architect Christopher Alexander in his book, A Pattern Language, talks about how “Balconies and porches that are less than six feet deep are hardly ever used”, in which case, “they might just as well not be there.” In flats and apartments, the balcony is the key connection to the outside. It is the garden, the courtyard and the aangan (front yard); a place to have your morning chai and hang your clothes to dry. In the Indian context however, it is common for people to close up balconies and create an additional room. One then begins to wonder if the balcony is too romantic an idea?

Moving further up, the terrace connects the house to the sky. The Gujarati word for terrace is ‘Agashi’. There are 2 ways in which its origin can be interpreted. The first, is that it came from Agras + as, meaning ‘open space’. The second, is that it came from Akashika meaning ‘light all over’. Traditionally, the terrace was an important place to do things that need sunlight during the day or cool air at night. One would dry papads, chilies, make pickles or even sleep on the agashi on summer nights and winter afternoons. Today, one sees the terrace being used for talking on the mobile phone (a private space, but out in the open), growing a small garden, having get-togethers etc.

With growing housing demands and competitive real estate markets, the threshold is now reduced to a door opening out into the corridor of an apartment. Living spaces are shrinking and the distinction between inside and outside is becoming starker. One will still find torans (auspicious garland over doorways) on the main doors and small rangolis in corridors as expressions or remnants of the Otla. In independent bungalows, compound walls separate the house from the street. Well, that’s fair enough, because streets have changed and so has our perception of a neighbourhood.

Till next time, one can hope and believe that one day, like the bollywood song, “Jhil-mil sitaron ka aangan hoga, rim-jhim barasta saawan hoga, aisa sundar sapna apna jeevan hoga….” (The front yard will be full of stars, there will be a slight drizzle of rain, our life one day, will be like this dream…)