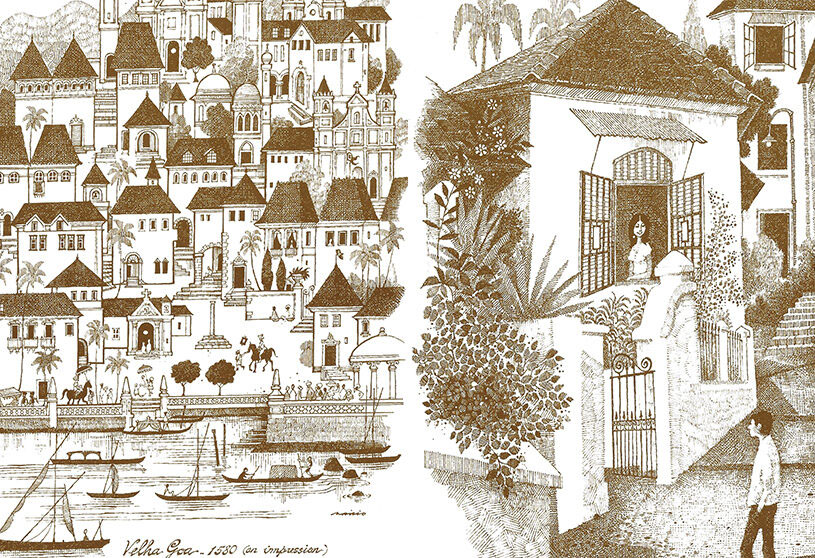

The year was 1982. Avinash and Geeta were a young couple who strongly believed in a minimalist lifestyle. They opposed the acquisition of excessive wealth and left their rich families to lead a simple life in a small Mumbai home. Avinash became a part-time writer and Geeta managed their home. Although not the best looking, their home seemed perfect to them. This is the context in which the song ‘Yeh tera Ghar, yeh mera ghar’ is positioned in the 1982 Bollywood film Saath Saath, starring Farooq Sheikh and Dipti Naval, both famous for portraying lives and aspirations of the middle class.

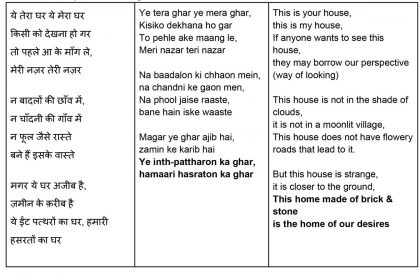

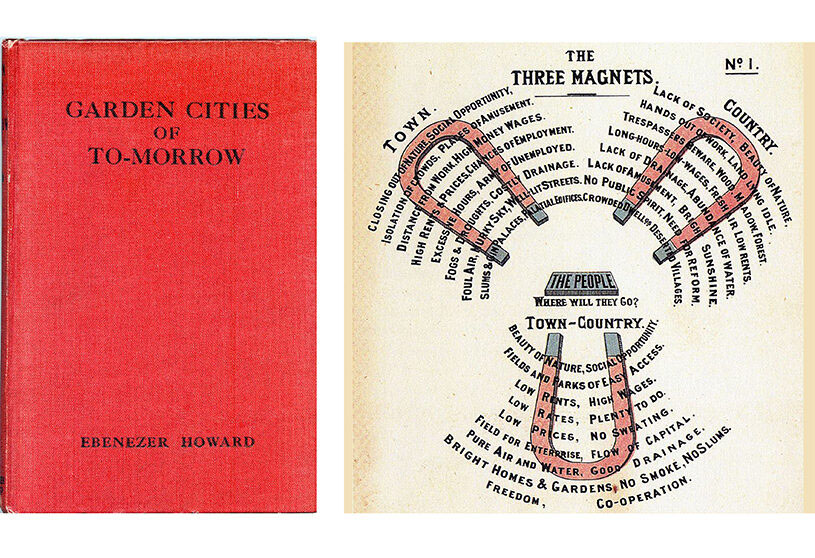

Here is an excerpt from the song:

The word ‘ghar’ is rooted in the Sanskrit word ‘grih’ which means ‘seizing the mind’, ‘stopping to move’, ‘to sit down’. So, the home is in essence a place to stop movement, a place to pause. There is a beautiful saying in Gujarati called ‘Dharti No Chhedo Ghar’, meaning, the end (last point) of the earth is the home. The word ‘makan’ on the other hand, usually refers to the physical structure. It is said to be borrowed from a Persian word that refers to ‘place’ or ‘location’. The same root produces the word ‘makam’, referring to a milestone in life or status in society.

It would not be wrong to suggest that the English equivalent of the word ‘ghar’ is ‘home’ and ‘makan’ is ‘house’. Both ‘home’ and ‘house’ are said to have their roots in the Germainic languages. Home is said to have originated from the Gothic ‘Haims’, meaning village, German ‘Heim’, meaning native land, Dutch ‘inheems’, meaning native, English ‘hamm’, meaning a piece of pasture land and Irish ‘coim’, meaning pleasant, among several other speculated origins. The word ‘house’ has its origins in old Germanic ‘khúsam’ which also produced German ‘haus’, Dutch ‘huss’ and Swedish ‘hus’. Some language specialists have argued that the word carries the meaning ‘to cover’ or ‘to hide’ and hence it is the root for other words like hide, hoard, and hut.

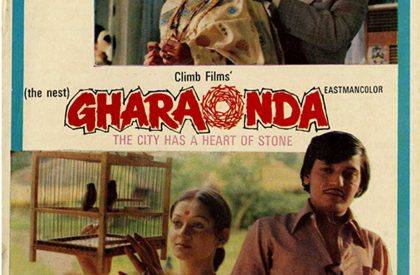

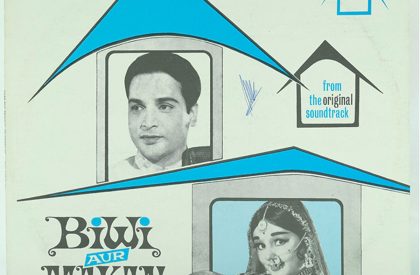

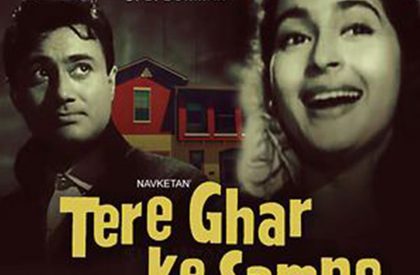

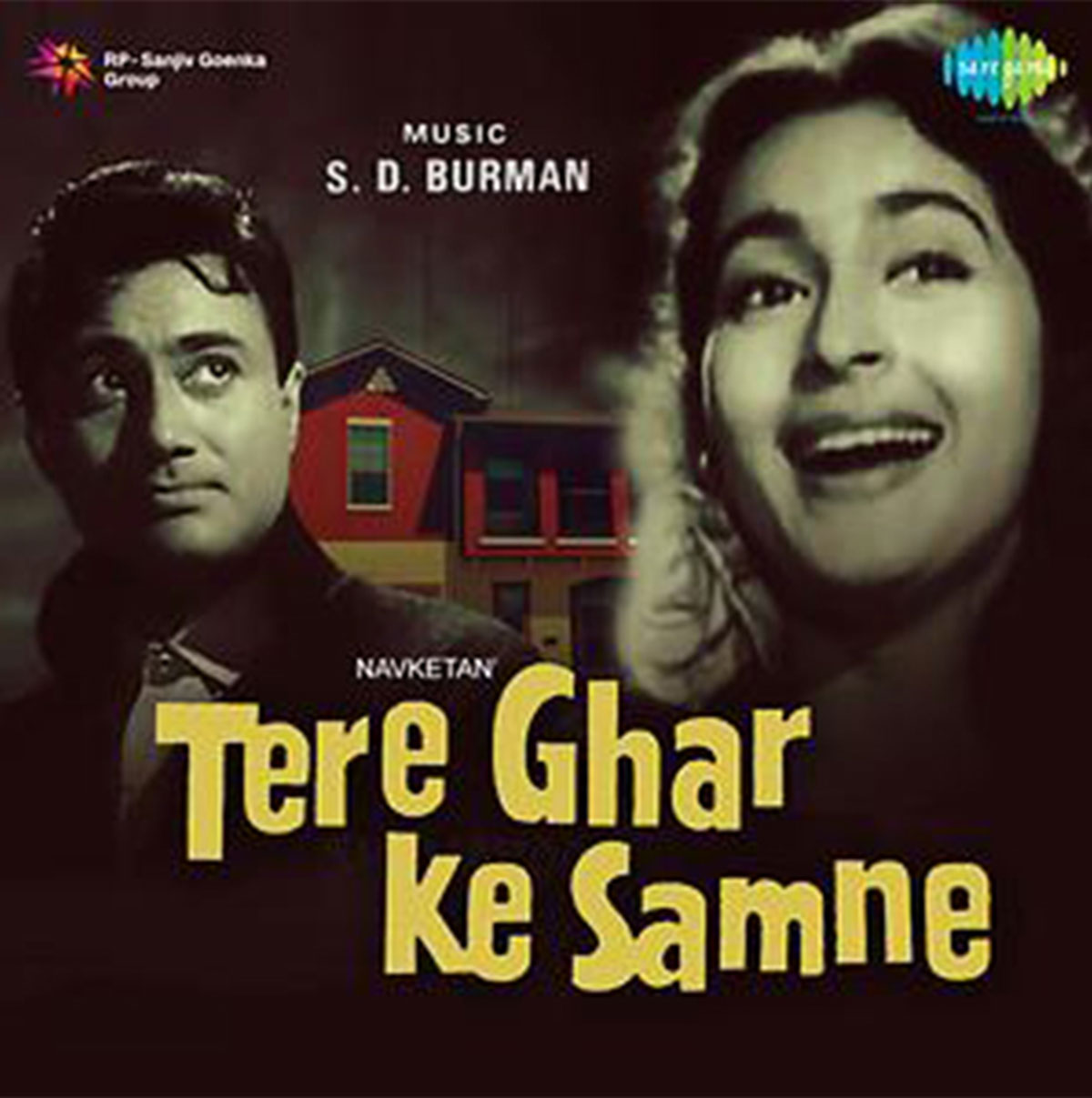

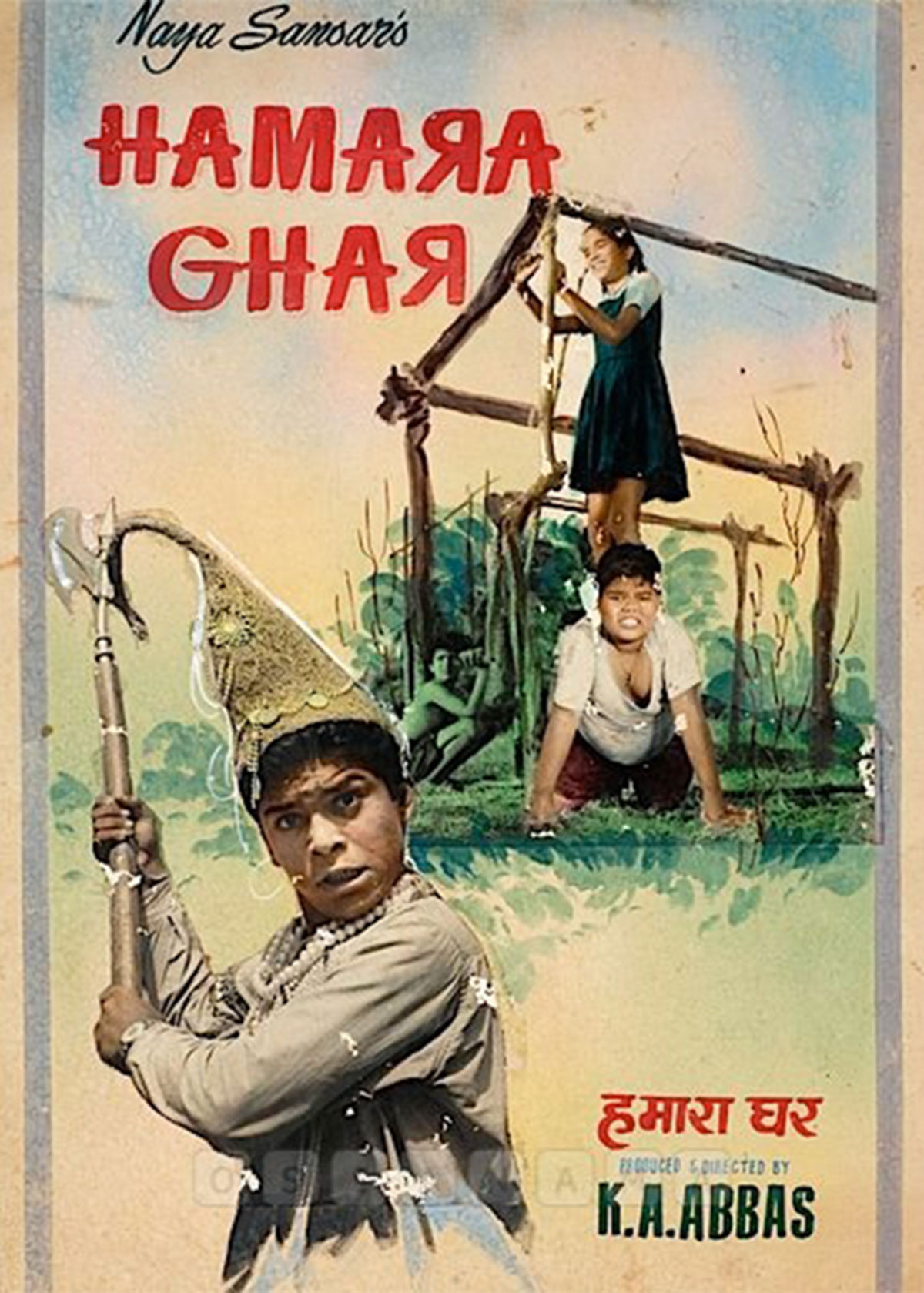

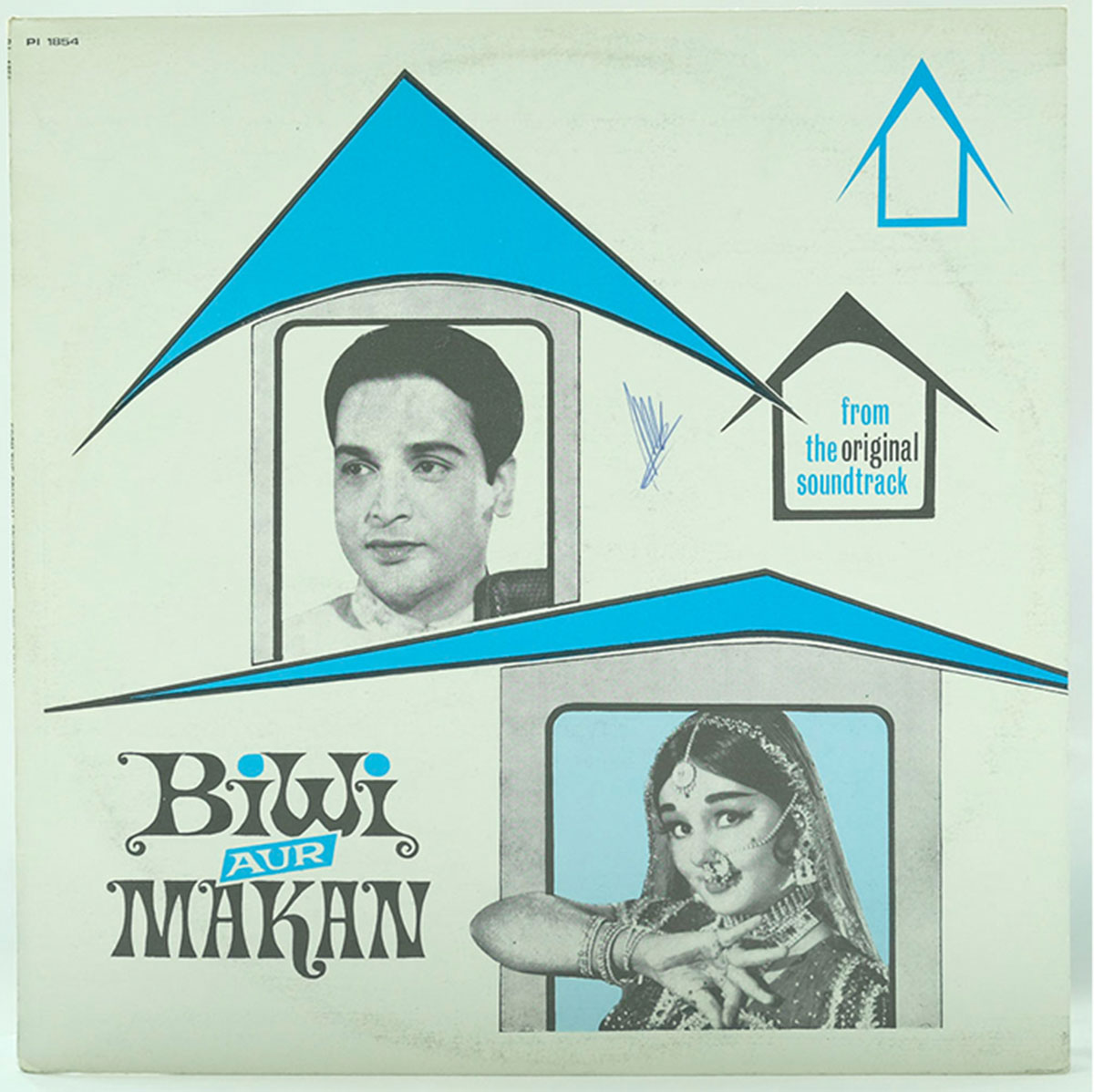

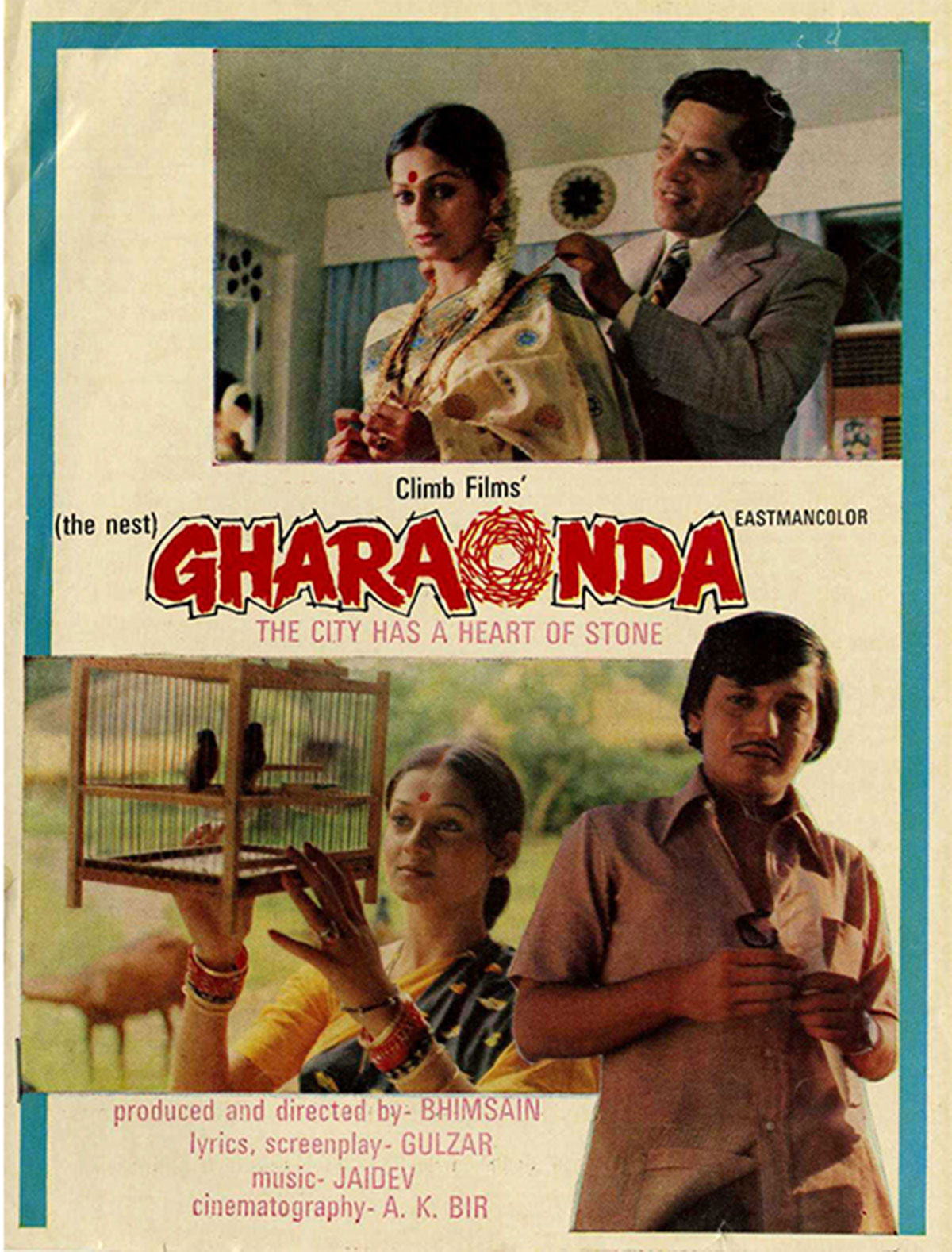

While makan and house connote the physical object, ghar and home seem to suggest the abstract association that one has with the object. It is the interaction of people with places/objects that generates architecture.The home acquires a meaning that goes beyond structural stability or aesthetics.The last 4 lines from the above excerpt “Magar ye ghar ajib hai, zamin ke karib hai, Ye inth-pattharon ka ghar, hamaari hasraton ka ghar” is probably hinting at this ‘place of pause’ – a place that is close to the ground and made of heavy materials like brick and stone. Over the years, Bollywood cinema has seen several movies like ‘Biwi aur Makaan’, ‘Hamaara Ghar’, ‘Gharonda’ and ‘Tere Ghar ke Saamne’, which place the house at the centre of the plot. The ghar can be ‘chota’ (small), ‘bada’(big), ‘ajeeb’ (strange), or ‘nyara’ (unique). Whatever the case may be, it has a special place in all our lives.

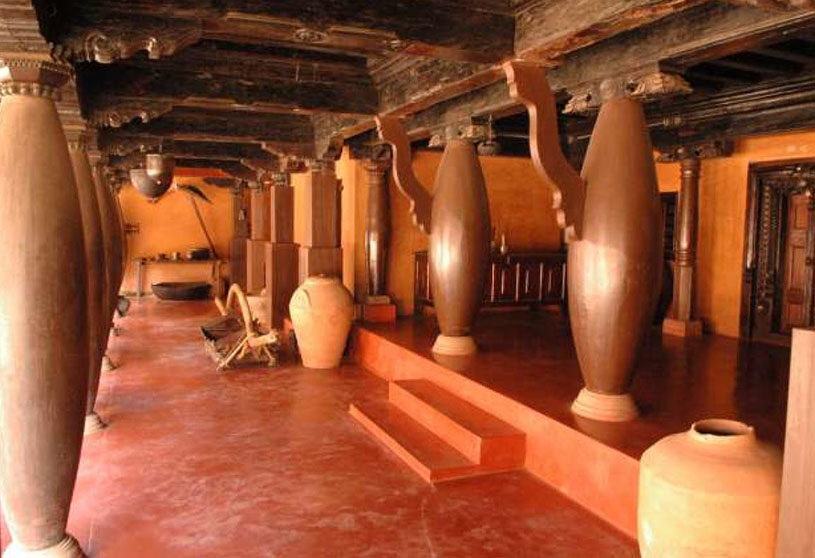

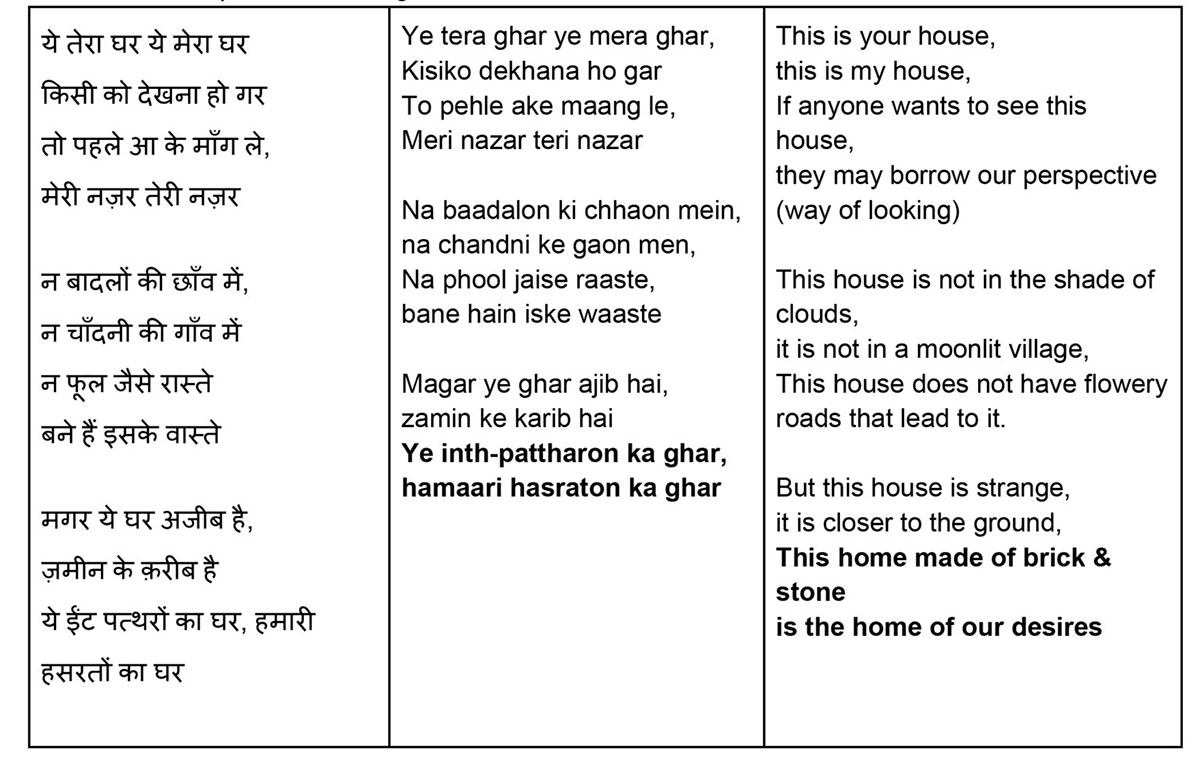

A home is not only a shelter but a manifestation of our aspirations, memories, emotions, identity, perceived status, beliefs, culture and so on. It has both material and abstract components. The material components include objects, furniture and building elements. The abstract components include ideas of ‘property’, ‘ownership’ and ‘identity’. This makes for such a beautiful piece of study. However, unlike the ‘English House’, where the origin of the 4 rooms (Living room, Bed room, Bathroom and Kitchen) are well documented, we in India are yet to produce a detailed region wise study of the evolution of house-form over the years. What kind of spaces did these houses constitute? What materials and building techniques were used? How did they vary from region to region?

Over the past century, building with cement concrete has transformed the builtscape all over India, most of which are houses. The material is now taken for granted, assuming every mason knows how to mix concrete. Concrete is easy to mix, can be moulded into any shape, is faster to build than other traditional materials and is promoted as strong and durable. Any Indian cement advertisement is sure to appeal to our emotions with its portrayal of cement as key to meeting the aspirations of the common man. Dutch architect Rainer de Graaf brings in a different perspective in his book ‘Four walls and a roof’. He says: “when I pause to look out the window. The vast majority of the built environment is unspeakably ugly: an infinite collection of cheaply made buildings engaged in a perpetual and bloodless contest over which can generate the most ‘interest’ for the lowest budget. Nothing more, nothing less. ‘Modern’ architecture—the kind of architecture most of us claim to profess—hasn’t helped; it has mainly proved to be a facilitator, an extension of the means to conduct this pointless contest, only at a faster pace.”

This impatience is taking a toll on our built environment. While some urban households are trying to revive lost practices of building with natural materials, rural Indian households aspire for the ‘pakka house’. ‘Pakka’ as a word has the same root as ‘pakana’ which means to cook. So, materials that constitute the house should be cooked eg. fired bricks. Materials play an important part in showcasing wealth, identity and status. The affluent Indians who were on trading terms with the English and French adopted the use of stained-glass windows. Cast iron railings, mangalore tiles, steel, cement concrete and other materials are great examples of those that travelled from one part of the world to the other and took a new form.

Philosopher and writer Alan Watts, in his lecture on ‘A True Materialist Society’ says “… you can’t have a nation or a society, in which everyone is always occupied in intellectual and computational pursuits. A few people have to be around who know how to handle the material world in a gracious way. And for these people we provide only regretfully, as an afterthought. The people who might otherwise be dropouts in high school should be given some courses which would prepare them for trades in carpentry, metallurgy, auto mechanics, furniture makers, cooks, and so on. But, as a rule—because these kinds of education in the academic world are provided only with regret, they are provided in a slovenly fashion.” We must value making as much as we value thinking. The ‘use and throw’ attitude is the opposite of what a true ‘materialist’ would profess. The entire Indian philosophy of ‘Charvak’ is dedicated to materialism and rejection of the non-material.

Till next time, keep looking and keep thinking because just like the JK Wall putty ad campaign, “Deewaren bol uthengi…” (the walls will speak for themselves). Every material has a story to tell.